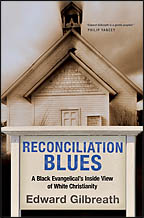

My friend Ed Gilbreath has just published a book: Reconciliation Blues: A Black Evangelical's Inside View of White Christianity.

My friend Ed Gilbreath has just published a book: Reconciliation Blues: A Black Evangelical's Inside View of White Christianity. Ed is the editor of Today's Christian and an editor at large for Christianity Today. In the late 90s he was associate editor for New Man, the official magazine of the Promise Keepers men's ministry. He is a coauthor of Gospel Trailblazer (Moody, 2003), the story of African American evangelist Howard O. Jones, the first black evangelist on Billy Graham's crusade team.

Ed's writing is mindblowing, so I'm very excited to read it. You can check out the prologue and first chapter online at ReconciliationBlues.com. Here's a bit from the book:

________

I’ve never thought of myself as "the token black," but I have enjoyed the privileges of being the only African American in the house. For a long time, I lived in blissful denial of the inadequacy of this arrangement. While certainly conscious of race, I didn’t consider it something that would affect people’s perceptions of me, nor did I allow it to influence my view of others. I wore color-blinders.

I was the approachable black guy, the white community’s friendly interpreter of all things African American. And hey, it was great! I admit it. At moments, I prided myself on being the only black person some white people would ever know personally. When another black person would come into the picture from time to time, I’d feel threatened—like they were trying to intrude on my territory. "These are my white people!" I’d think.

The problem, of course, is that no single person can legitimately represent an entire race. Though I lived with that delusion throughout much of my young adulthood, I got a rude awakening once I began to ascend the professional ranks at white evangelical institutions. After a period of racial hibernation, I awoke to the reality of my otherness. I realized once and for all that, as an African American evangelical, I am a black Christian in a white Christian’s world.

________

2 comments:

I read the first chapter of this book. Wow! He hits it right on the head. Before I read it, I was thinking to myself the real problem with white evangelicalism is in its ethnocentrism. It tends to be a very homogonous group socio-economically, politically, racially, etc. There is so much that white evangelicals can learn from the black church, the Latino church, and the overseas church. Yet, I think many white evangelicals exist in a bubble of cultural isolation. That isn't the main problem, however. The main problem is the accompanying underlying notion of cultural superiority. Most white evangelicals when confronted with the notion of cultural superiority would totally deny it. The reason is that most are oblivious to the fact they hold their brand of Christianity to be THE right form. The author gets it right when he says, "But it also has meant living within a religious movement that takes for granted its cultural superiority."

I am white, and I grew up in a largely Latino community. I went to predominantly Latino schools and churches. Because of this, when I am in an "all white" environment, I am probably a little more keen to many of the subtle comments, derogatory remarks, and feelings of superiority. I have been in situations where other white folks have said things in my presence that they would definitely not say if a person of color was around. One time at a Christian retreat, a retired pastor started talking about how Hispanics are so rude because they never show up to meals on time. He said this in the presence of my fair-complected wife who is a 100 percent, born-in-East-LA Chicana. The man assumed she was white. He walked out of the room and I practically had to drag my wife outside and calm her down because she was ready to go off on the poor old ignorant man when he returned. I was kind of in this weird position of trying to defend his ignorance. I told her that at his age, he was not going to change his views. "He really didn't mean it that way." I knew the guy, and he was really a nice man and he would never think of himself as prejudice. In his public interactions with Latinos, he was always very nice. He simply made a judgement based on a feeling that his own value--derived from the culture in which he was raised--of being prompt is superior.

A friend once greatly educated me by telling me this: Every person has a tendency to judge others based on the norms of our own lives. So if someone does something differently from us, we tend to respond by saying, "That's weird" or something similar. Funny thing is, what's "weird" to one person is likely normal to a very large group of people. For example, a Vietnamese co-worker used to bring traditional Vietnamese foods for lunch. Every day, several co-workers made a big deal of what she was eating. Some would look a little disgusted, some would say, "What's in that?" with that certain tone of disapproval. One, who actually sampled my friend's lunches and really liked the food, still regularly told her, "You bring the weirdest stuff." Now, if my friend was eating with her family or dining in a Vietnamese restaurant, no one would even notice her meal. To a whole lotta Vietnamese people around the world (and even people of other ethnicities who happen to love Vietnamese food), this food was just normal.

And as I've learned, this isn't just an "ignorant white people" problem. I've heard plenty of derogatory comments about white people, perhaps because the commenter didn't know I was half white. I'm multi-ethnic, so I get a little on both sides, from, "You're not really white," to "I see you as a white person," to "I don't think of you as any ethnicity--you're just my friend." That last comment perhaps comes from seeing everyone as the collective body of Christ, and that's a good place to start. Yet I hope we can push ourselves beyond that to acknowledge and learn about each individual limb, organ, system and cell within the body.

I've come to recognize people have unique experiences, and these go way beyond ethnicity. We've all grown up in different states or countries, during different decades, and we're from different economic backgrounds. And I believe we need to be curious and ask questions when we don't understand why someone does something differently--as long as we ask in the right way. We need to approach others humbly, like students who long for an education, with an appreciation for the experiential knowledge others possess. We need to accept that every individual is different, and those differences aren't weird, odd, or wrong. We're all a little ignorant, and each of us equally has something to teach.

Post a Comment